Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet

On November 17, author Jamie Ford speaks at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater in Bloomington for the NEA Big Read and the library’s biennial Power of Words program.

As he often does, Jamie Ford writes about the clashing and melding of different cultures in his three historical novels: Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, Songs of Willow Frost, and Love and Other Consolation Prizes.

In Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, Ford presents a tender love story of two children, each from a minority community during WWII. We first meet Henry, the twelve-year old only child of parents born in China. His father, a leader in Seattle’s Chinese community, spends his free time tracking the battles that Japan wages in China.

Henry’s parents force him to attend an almost all-white school on scholarship: they desperately want him to become “an American.” To this end, when Henry turns twelve, his father refuses to let him speak Cantonese at home. But as neither of his parents speak English, this puts a dent in family communication, and leaves Henry feeling lonely and isolated. To make matters worse, bullies at school beat Henry up nearly every day, though he does get a partial reprieve by serving lunch next to the caustic but caring Mrs. Beatty, the cafeteria supervisor.

One day, a young Japanese, girl, Keiko, joins Henry on the serving line. The two draw together, and Henry soon protectively walks Keiko home after school. He shares with her his intense love for jazz and his friendship with Sheldon, a black street busker from the American South who recognizes prejudice and racial abuse all too well. Before long, Henry asks Keiko in Japanese, “How are you today, beautiful?”

But even as they grow closer, sharing an innocent kiss, around them war-flamed racial hatred grows. Henry’s father insists that the young man wear a pin that says, “I am American”; in Nihonmachi (Seattle’s Japan town), shopkeepers post signs reading "American-owned." Yet nothing stops the anti-Japanese sentiment.

Soon, President Franklin Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, allowing military leaders to designate "military areas" that exclude from them whomever they chose. Consequently, one day Henry sees a long line of people forced to march to the train station—the first large group of Japanese interns under the new law.

Keiko gives Henry her family’s photograph albums and asks him to save them for her, creating a crisis at home for him when his parents discover them. He must choose between the family that raised him and his friend’s Japanese-American family, who are shortly removed to Puyallup, the Washington State Fair site, where they sleep in former horse stalls.

This moving novel shows the evil governments can do during wartime, pitting ethnic group against ethnic group. It's also a father and son novel, a young love story, and a homage to that unpredictable musical art, jazz. A fine book.

Read Hotel at the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, then come hear what the author, a Chinese-American himself, shares about its history, and his process of writing it.

Long before humans created written records of life on Earth, the fossil record told its own fascinating story. The

Long before humans created written records of life on Earth, the fossil record told its own fascinating story. The

Surrealism has its roots in the

Surrealism has its roots in the  After a head injury in World War I, Guilliaume Apollinaire underwent surgery that saved his life. But friends felt it also changed him, from bold, exuberant, and openhearted to cautious, even suspicious at times. The literary and social rebel began talking openly of his desire to be accepted by the staid

After a head injury in World War I, Guilliaume Apollinaire underwent surgery that saved his life. But friends felt it also changed him, from bold, exuberant, and openhearted to cautious, even suspicious at times. The literary and social rebel began talking openly of his desire to be accepted by the staid  Along with Soupault and Aragon, Breton met often with Paul Eluard and his wife Gala, Robert Desnos, René Crevel, Benjamin Péret, and Antonin Artaud—to name a few who passed through those doors of the Certa Café in Paris. Together, they explored dream, seance, trance, automatism, sleeping fits, and “the receptiveness of chance," using every technique to break the chain of thought, to find new associations, new meaning.

Along with Soupault and Aragon, Breton met often with Paul Eluard and his wife Gala, Robert Desnos, René Crevel, Benjamin Péret, and Antonin Artaud—to name a few who passed through those doors of the Certa Café in Paris. Together, they explored dream, seance, trance, automatism, sleeping fits, and “the receptiveness of chance," using every technique to break the chain of thought, to find new associations, new meaning.

The group came up with a game called Exquisite Corpse, and published automatic texts called Soluble Fish. Convening what they called the Congress of Paris, they tried to spread their ideas further by opening a Bureau of Surrealist Research, publishing journals like La Révolution Surréalist, Le Surréalisme au Service de la Révolution, and the International Bulletin of Surréalism.

The group came up with a game called Exquisite Corpse, and published automatic texts called Soluble Fish. Convening what they called the Congress of Paris, they tried to spread their ideas further by opening a Bureau of Surrealist Research, publishing journals like La Révolution Surréalist, Le Surréalisme au Service de la Révolution, and the International Bulletin of Surréalism.

A Library book's life is not one of leisure. Over 2,000 books (out of a total collection of over 330,000) are checked out on a typical day, and another 1,700 checked back in. A given copy of a book averages about 50 checkouts; by that time, it's likely to be too worn to be suitable for lending. So we keep multiple copies of our most popular titles—which is good, considering that a favorite like The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss has been through many copies and checked out over 2,500 times (the only one of the top five children's titles that isn't a Seuss classic? Frog and Toad All Year, by Arnold Lobel).

A Library book's life is not one of leisure. Over 2,000 books (out of a total collection of over 330,000) are checked out on a typical day, and another 1,700 checked back in. A given copy of a book averages about 50 checkouts; by that time, it's likely to be too worn to be suitable for lending. So we keep multiple copies of our most popular titles—which is good, considering that a favorite like The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss has been through many copies and checked out over 2,500 times (the only one of the top five children's titles that isn't a Seuss classic? Frog and Toad All Year, by Arnold Lobel).  Once returned to the Library, a book slides down a chute and onto a sorting machine that automatically checks it back in, and then sends it to a bin. From there, Library Staff sort books onto carts, then roll them back out to the shelves. Then they're found again by readers of all kinds—and the process begins again.

Once returned to the Library, a book slides down a chute and onto a sorting machine that automatically checks it back in, and then sends it to a bin. From there, Library Staff sort books onto carts, then roll them back out to the shelves. Then they're found again by readers of all kinds—and the process begins again.

Monroe County Public Library. We're all about making and creating in our community, so of course we've got a booth at Makevention. Stop by and say "Hi"—and try out our virtual reality setup, LEGO building station, 3D printer, and more.

Monroe County Public Library. We're all about making and creating in our community, so of course we've got a booth at Makevention. Stop by and say "Hi"—and try out our virtual reality setup, LEGO building station, 3D printer, and more.

Castlemakers is a Greencastle makerspace who host an annual mini-golf design competition. Enjoy their course—and see what else they’re up to.

Castlemakers is a Greencastle makerspace who host an annual mini-golf design competition. Enjoy their course—and see what else they’re up to.

This is just a small sampling of what’s in store this Saturday. Also keep your eye out at Makevention for old-school geekery like ham radio, calligraphy, weaving, and swordplay—and future-facing stuff like sentient architecture, microconrollers, and 3D printing. You can even try your luck at getting out of the escape room, a unique structure designed to test your wits and patience.

This is just a small sampling of what’s in store this Saturday. Also keep your eye out at Makevention for old-school geekery like ham radio, calligraphy, weaving, and swordplay—and future-facing stuff like sentient architecture, microconrollers, and 3D printing. You can even try your luck at getting out of the escape room, a unique structure designed to test your wits and patience.

"Beautiful like the chance meeting on a dissection table of a sewing machine and an umbrella." —Compte de Lautréamont

"Beautiful like the chance meeting on a dissection table of a sewing machine and an umbrella." —Compte de Lautréamont

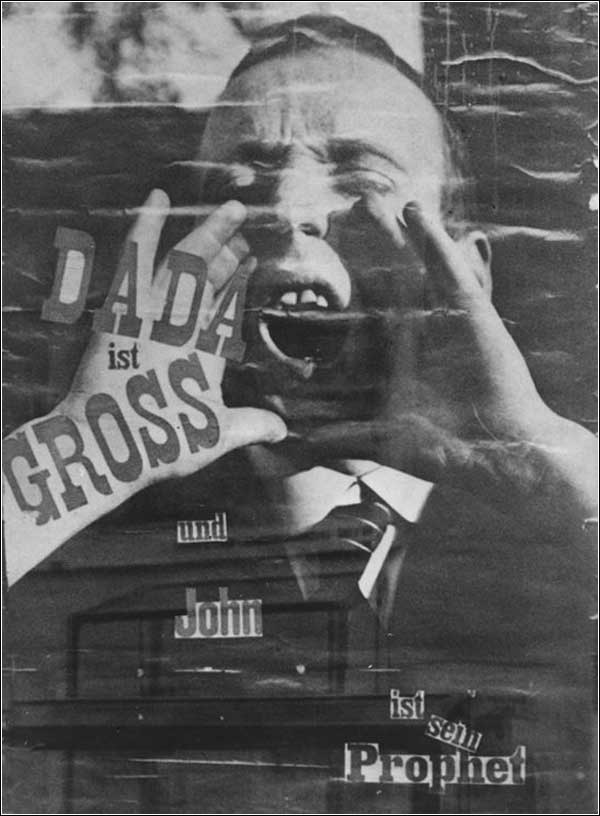

Evenings at the Cabaret Voltaire were tame until the arrival of Ball’s friend Richard Huelsenbeck, who had come from Berlin to study medicine, or so he’d told his draft board. He immediately joined the inner circle of the Cabaret Voltaire, adding an element of youthful arrogance, immediacy, confrontation, and violence.

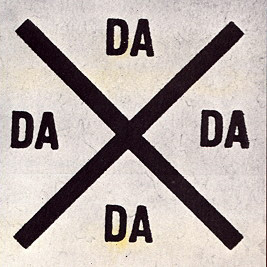

Evenings at the Cabaret Voltaire were tame until the arrival of Ball’s friend Richard Huelsenbeck, who had come from Berlin to study medicine, or so he’d told his draft board. He immediately joined the inner circle of the Cabaret Voltaire, adding an element of youthful arrogance, immediacy, confrontation, and violence. As the new leader, in July 1917 Tzara proclaimed, “The DADA MOVEMENT is launched” in the first issue of the movement's eponymous magazine. He brought new members into the fold locally, while exchanging letters, books, and poems with Marinetti in Italy, Apollinaire and Jean Cocteau in Paris, Francis Picabia in New York City and Barcelona, Andre Breton near the French front, Max Ernst on the German front, and many others.

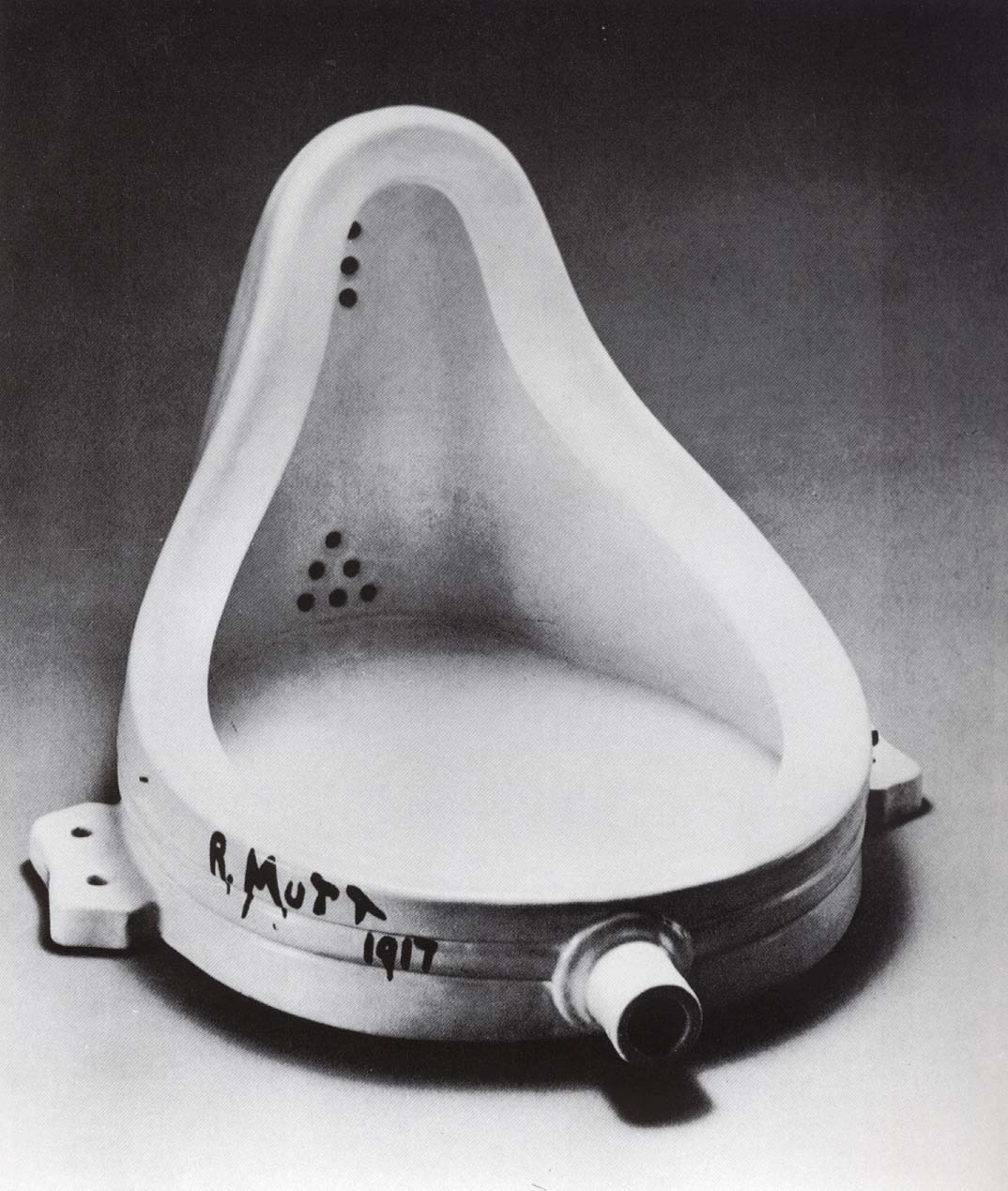

As the new leader, in July 1917 Tzara proclaimed, “The DADA MOVEMENT is launched” in the first issue of the movement's eponymous magazine. He brought new members into the fold locally, while exchanging letters, books, and poems with Marinetti in Italy, Apollinaire and Jean Cocteau in Paris, Francis Picabia in New York City and Barcelona, Andre Breton near the French front, Max Ernst on the German front, and many others. With Picabia, Duchamp organized the only known DADA event in New York City at the Grand Central Gallery, where they invited provocateur Arthur Cravan, a boxer, poet, burglar, forger, and nephew of Oscar Wilde, to give a talk. Calling himself “the poet with the shortest hair in the world,” Cravan had published a precursor to DADA in Paris called Maintenant, wherein his wicked, vituperative wit earned him a beating by a crowd of his rivals.

With Picabia, Duchamp organized the only known DADA event in New York City at the Grand Central Gallery, where they invited provocateur Arthur Cravan, a boxer, poet, burglar, forger, and nephew of Oscar Wilde, to give a talk. Calling himself “the poet with the shortest hair in the world,” Cravan had published a precursor to DADA in Paris called Maintenant, wherein his wicked, vituperative wit earned him a beating by a crowd of his rivals. Francis Picabia was a cubist painter and a very rich man who collected fast automobiles and fast women. He was extravagant, outgoing, bored, and independent of thought, with a love for a well-turned prank. He reached for the excessive and embraced the paradoxical.

Francis Picabia was a cubist painter and a very rich man who collected fast automobiles and fast women. He was extravagant, outgoing, bored, and independent of thought, with a love for a well-turned prank. He reached for the excessive and embraced the paradoxical. and inciting the crowd to his own near-lynching. The owner of the room threatened to call the police, but was persuaded by members of the audience to let Huelsenbeck have his say. He ended the evening with a spirited reading of his always-provocative

and inciting the crowd to his own near-lynching. The owner of the room threatened to call the police, but was persuaded by members of the audience to let Huelsenbeck have his say. He ended the evening with a spirited reading of his always-provocative  The climax for Berlin's DADA was the First Annual DADA Fair (Dadamesse) in June of 1920. Exhibits included a mannequin suspended from the ceiling dressed in uniform and sporting a severed pig’s head, and a female mannequin sporting an Iron Cross on its rear end.

The climax for Berlin's DADA was the First Annual DADA Fair (Dadamesse) in June of 1920. Exhibits included a mannequin suspended from the ceiling dressed in uniform and sporting a severed pig’s head, and a female mannequin sporting an Iron Cross on its rear end.

Bill Sherman, who’s taught virtual reality at IU since 2000, says that thanks to shrinking costs and ever-improving technology, we’ll soon see amazing developments on both fronts. “The headsets will become less clunky, and won’t even be full headsets at some point,” making VR gaming less restrictive, he said. And as science and medicine continue to utilize virtual reality, the benefits of being “inside” the worlds under study have led to new discoveries and innovations. “Even statisticians are doing more informed research by literally seeing their data from different angles, and psychologists are already treating things like phobias with VR, by exposing people to virtual heights and snakes and things in a controlled and safe way,” said Bill.

Bill Sherman, who’s taught virtual reality at IU since 2000, says that thanks to shrinking costs and ever-improving technology, we’ll soon see amazing developments on both fronts. “The headsets will become less clunky, and won’t even be full headsets at some point,” making VR gaming less restrictive, he said. And as science and medicine continue to utilize virtual reality, the benefits of being “inside” the worlds under study have led to new discoveries and innovations. “Even statisticians are doing more informed research by literally seeing their data from different angles, and psychologists are already treating things like phobias with VR, by exposing people to virtual heights and snakes and things in a controlled and safe way,” said Bill.